features

The history of fish and chips – who invented the UK’s beloved chippy tea?

23 Sept 2022

8m

There is undoubtedly no takeaway more beloved in the UK than fish and chips. In fact, figures show that Brits consume 382 million meals from fish and chip shops every year, with almost a quarter of the UK visiting their local one at least once a week.

Simply comprised of a battered fish and big, fluffy chips, a chippy tea doesn’t put on any airs or graces, and that’s the essence of its charm. Grab it wrapped in a paper and soak it in salt and vinegar – it’s portable, scoff-able and (at least sometimes) affordable.

What’s fascinating is that our love for fish and chips is actually one of the most enduring food relationships we have in this country. It was the UK’s first takeaway option, and it’s a dish that remains synonymous with us around the world today.

But who should we thank for putting the humble chippy on the map? Let’s explore where fish and chips originate from, and dig into the dish’s little known history…

Fish and chips is undoubtedly one of the UK’s most beloved national dishes (Credit: Alamy)

Where did fish and chips come from?

It’s hard to imagine a time when battered fish and chips didn’t belong together, but before they were a duo, they both had to rear their heads on the global food scene.

Fried fish was first brought to the UK by Jewish immigrants who settled here in the early 16th century, typically cooked in oil and batter on Fridays so that it could also be eaten the next day on Sabbath. The batter was supposed to preserve the fish, so it could be eaten when they weren’t religiously permitted to prepare new meals.

Whilst fried fish was commonly eaten by Jewish people across the world at this time, some historians claim that the first battered fish consumed in the UK came specifically from Sephardic Jewish immigrants from Spain and Portugal, noting the similarities to ‘Pescado frito’ (fish coated in flour and fried in oil).

“What seems to happen is by the 18th century and the early 19th century you have books which talk about fried fish ‘in the Jewish style’,” says Professor Panikos Panayi, an expert in European history and author of Fish and Chips: A History. “This coincides with newspaper reports about Jewish fish sellers, especially in east London, and from detailed descriptions of people visiting these shops we know it is the sort of fish we would recognise today.”

Indeed, Claudia Roden’s The Book of Jewish Food, notes how Thomas Jefferson tried “fish in the Jewish fashion” during a trip to London, and in his 1845 cookbook, A Shilling Cookery for the People, French cook Alexis Soyer also details the “Jewish manner” of cooking fish with oil rather than meat fat.

“There were a series of key technological developments in the nineteenth century [that majorly escalated the amount of people eating fish],” says Professor Panayi.

For one, consumption of fish became more common in the UK when trawl fishing in the North Sea begun, but the biggest game changer was the high speed rail.

“With high speed rail more available, from about the 1840s, everyone could have fresh fish in about two hours. That changed everything”.

Fried fish being sold in east London’s Petticoat Lane Market in 1909 (Credit: Alamy)

Now, what about the potato? Its history is a little murkier.

“With regard to the potato, it entered Europe in the sixteenth century, [and whilst it was adopted in Ireland earlier,] I think most people would agree they don’t really take off as a staple in Britain until the early 19th century.

“The reason for that is that during the Napoleonic War, the price of grain goes up and that starts the process of the move towards potato eating, particularly among the working class,” Professor Panayi adds.

As for how it transitioned into the chip we know and love today? Here lies a little more debate.

Several historians cite that deep-fried, cut potatoes were invented in Belgium, and came about as a replacement for fish when it was difficult to source. However, Professor Panayi says he believes chips to have derived from french fries, which begun to circulate over from (you guessed it), France, by the 18th century.

What we do know is that chips as we know them today were being consumed in the UK by 1859, as Charles Dickens gives us the first reference to them in A Tale of Two Cities, writing of “husky chips of potato, fried with some reluctant drops of oil”.

“By the second half of the 19th century, chips become more widely eaten in continental Europe, and fried potatoes arrive in Britain,” the historian says.

As for who paired fish and chips together? That’s a whole other conversation…

Who invented fish and chips?

Fish and chips is served all across the UK today (Credit: Alamy)

Whilst this is a topic which is also hotly debated, most historians concur that fish and chips were paired together by Jewish immigrant, Joseph Malin in 1863. This account is also verified by the National Federation Of Fish Friers, who contacted 120 regional associations in 1965 (basically, they did their homework).

Malin had a fish and chip shop on Old Ford Road in Bow, east London, and it was so successful it served locals the national delicacy for over a century.

His status as the inventor of ‘fish and chips’ is contested by Lee’s Chipped Potato Restaurant in Lancashire, which also claims to be the first to have sold the two food items together.

Discussing this claim, historian Professor Panayi says research suggests fish wasn’t being served there alongside chips until after Malin set up shop.

Another shop in Tommyfield market in Oldham also claims to be the UK’s ‘oldest fried chip shop’, and whilst historian acknowledges that chips may have come first in the North, due to differing prices of grain, he believes “this transfer of food from the mainstream Jewish community to a gentile society almost inevitably had to take place in east London.”

What nobody can dispute is that after the fish and chips combo was invented, it took off incredibly quickly, and by the 1900s, the meal was “universal” across Britain.

By 1935, the UK housed over 35,000 fish and chip shops (including one in Bradford that had to employ a doorman to manage the queues), and it was the only food not to be rationed in either World War.

Fish and chips was such a well loved pair that some historians report British soldiers even identified each other during the ‘D’ Day landings by calling out ‘fish’ and then waiting for the other to reply ‘chips’.

Professor Panayi cites the fact the meal was “cheap” as a key reason it became so popular. Plus, he says, it was an efficient way for workers to eat “real food” and get nutrition quickly, around a time when most people did manual work.

It might sound hyperbolic, but it has even been asserted that Britain won the first World War because its soldiers were fed fish and chips in the trenches, whilst Germany was blockaded and didn’t have access to the same nutrition.

God bless the chippy, ey?

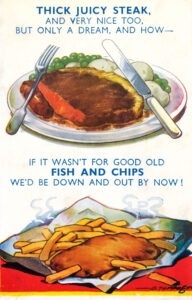

This wartime illustration proves the nation’s dependence on the humble chippy (Credit: Alamy)

What happened to fish and chips wrapped in newspaper?

Before the 1980s, fish and chips were often wrapped in newspaper in order to keep prices low, however, the practice has almost entirely been phased out now.

The practice has stopped because it was ruled that doing so was unsafe, as the food came in contact with newspaper ink. Believe it or not, doing so was actually made illegal under the 1990 Food Safety Act.

Nowadays, you’ll likely see chippies serving their fish and chips in food wrapping paper, polystyrene or recyclable cardboard boxes. In order to keep things traditional, some shops cheat a bit and keep a layer of newspaper on the outside, making sure that there’s a layer of wrapping paper in between.

What fish is used to make traditional fish and chips?

The main requirement when cooking fish and chips is that you use a white fish. Professor Panayi says that research suggests plaice was used in fish and chips most commonly when the dish was first eaten, but this changed to cod by the beginning of the 20th century.

Cod still forms the basis of a typical chippy tea today (largely due to its affordability), whilst haddock is also commonplace in fish and chip shops up and down the UK.

While less traditional, it isn’t uncommon for fish and chip shops to sell other white fish, too, like pollock, hake, plaice (as in the old days), and skate, huss or ray. Northern Ireland and some parts of Scotland also often serve whiting.

Fish and chips usually come wrapped in newspaper (Credit: Alamy)

What batter is used to make traditional fish and chips?

As for the batter, this has changed a little over the years, too.

The Professor recounts fish friers telling him they used rice flour in the first few decades of fish and chip mania, and “by the end of the 20th century you could buy ready made batters as well.”

If you’re looking to make a traditional fish and chips batter from scratch, most recipes dictate that you just need water and plain flour, with a dash of baking soda and vinegar to lighten it up and make it bubbly.

Modern iterations of this include beer, although you wouldn’t have seen such a thing back in the day. Contemporary fish friers have discovered that using beers not only gives fried fish its distinctive orange colour, but it also alters the batter’s taste. Some places add larger, whilst others add stout and even bitter to the mix.

How to make traditional ‘chippy’ chips

Chips are the ingredient that vary the most in fish and chip shops across the UK, and Professor Panayi says there is less uniformity when it comes to a consensus over how they were served back in the day.

Today, anyway, ‘chippy chips’ are usually thicker than french fries, like you’d find in the States. They would have typically been cooked in lard, however now it’s more common to see them fried in vegetable oils, due to the high smoke point.

Chippy sides have evolved over the years (Credit: Alamy)

What to have with fish and chips

“Especially in the last three decades, fish and chip shops have diversified in order to survive,” Professor Panayi explains.

Today, you’ll see chippies selling everything from burgers to kebabs as well as their bread and butter. This is because, as takeaway culture has boomed, we’re used to more choice and variety.

Whilst salt and vinegar has long been the most traditional accompaniment, it’s rare you’ll go to a chippy that won’t offer other toppings too, like curry sauce, gravy, baked beans and mushy peas.

Some of these combinations are particularly popular in certain areas of the UK, for instance, the Midlands call chips and mushy peas a “pea mix” and chips with beans a “bean mix”.

You’ll almost always find side orders in your chippy these days too, like scraps (pieces of batter leftover from frying the chips), potato cakes and Saveloy sausages.

All these tweaks to the humble chippy show how much our tastes have evolved over the years. Nobody can dispute that fish and chips are great on their own, but in this day and age you can slather your chips in all sorts.

One thing is consistent, though – no matter if you pile it high or eat it as it comes, the wonder of a chippy tea truly knows no bounds.

.jpg_dU0O4c?tr=w-2560,f-webp,q-70)